Religion

In Tsimba’s body of work, the spectre of religion is indubitably present and criticised, as it can serve in the annihilation of personal power. In Congo, religion has always played an essential role in subjugating minds. It erases ancestral memory and affects imaginations. For religion, paradise is the ultimate goal and earth must be set aside. Freddy Tsimba challenges this premise. (In Koli Jean Bofane)

In 2011, a Revival church (in French, Église du Réveil, literally Church of the Awakening) opened beside Freddy Tsimba’s atelier in the Matonge quarter of Kinshasa. The air was rapidly filled with the sound of sermons, making it impossible to work in peace. Exasperated by the incessant noise, Freddy Tsimba created this work and installed it in front of his property, in full view of everyone. The church, horrified by it, decided to move elsewhere. This work is the first of a series of 9 women, all seated, with crosses piercing the body.

Freddy Tsimba (1967), Réveil Sommeil (Revival Sleep). 2011. Scrap materials, found spoons, knives, and chair. Collection Gervanne and Matthias Leridon. Photo © Mathieu Lombard. Courtesy Collection Gervanne and Matthias Leridon.

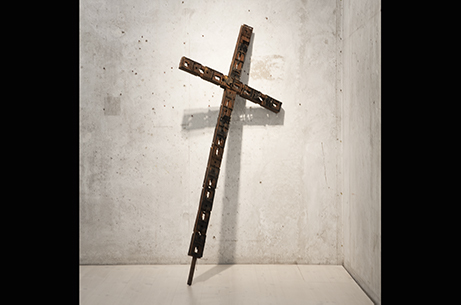

This work, created in Kinshasa, is part of a larger chapel. The project ‘Les archives suédoises’ was initiated by the artists Anna Ekman and Cecilia Järdemar around an archive of glass negatives from the Swedish missions of the then Belgian Congo (between 1890 and 1930). With Freddy Tsimba, they investigated what alternative readings of history could take shape when the archives were used as a starting point. Freddy Tsimba’s father was educated in a Swedish mission.

Freddy Tsimba (1967), Croix (Cross). 2018. Scrap materials, mousetraps. ‘Les archives suédoises’ project. Kalmar, Konstmuseum, Sweden. Artist’s collection, Ghent.

Face to face

With religion looming, the museum’s collections, photos, and objects reflect the extent of Catholic and Protestant presence in Congo since the 16th century.

In 1483, during the reign of King Nzinga Kuvu, the Portuguese created commercial and cultural ties with the local populations and evangelized them. Smiths then crafted Kangi Kiditu brass crucifixes depicting Christ on the cross. Adorned with orants, they reflected the syncretism that took place between the traditional and the new religion. They became insignias of nobility and chiefly prestige and lineage.

The Kongo crucifix (Kangi kiditu), produced between the 16th and 19th century, is proof of the first evangelisation and the introduction of Christianity to the Kongo kingdom. The traditional Kongo religious system postulated the existence of a lone supreme God who created the universe. The ancestors, cultural heroes, and nature spirits were just as important. This Christian-inspired crucifix was used as an object of devotion in the same way as statues of the Virgin Mary and medals of saints.

Kangi kiditu. Crucifix. Kongo central, RD Congo. [Kongo]. s.d. Wood, copper, brass. Gift from Les Amis du MuséeHO.1963.66.1, collection RMCA Tervuren; photo J. Van de Vyver © RMCA Tervuren.

This Christian-inspired crucifix represents a female Christ with a baby on her back. It is a local interpretation of maternity figures used to invoke fertility. It symbolizes birth and is proof of the syncretism between the traditional and the new religion.

Crucifix with mother and child. Kongo central, RD Congo. [Kongo]. 19th century. Brass. HO.1973.48.1, collection RMCA Tervuren ; photo © RMCA Tervuren.